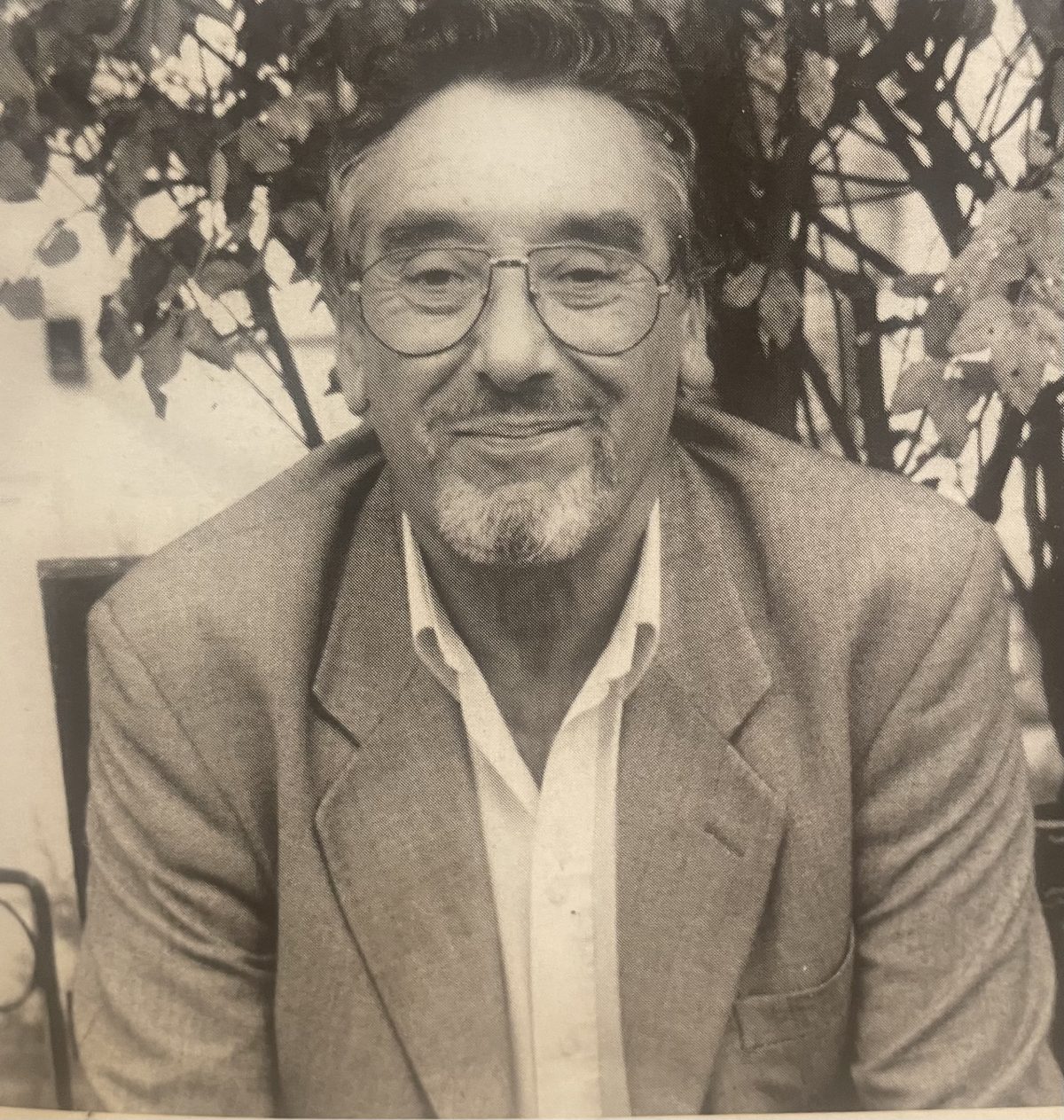

TONY

WILSON

PLACE

Cultural Manchester adores the legacy and memory of Anthony ‘Tony’ Wilson. His urbane confidence, fierce wit and sharp humour imbued the city, or at least the people he encountered, with a metropolitan confidence.

As Wilson’s biographer, Paul Morley, has written, (Tony’s) ‘occupation was Manchester’. Andy Spinoza, Manchester businessman and writer, has written how Salford-born Wilson’s life was ‘packed with provocations, infatuations, successes, tragedies and controversies…in any account of the city from the seventies to the noughties you keep coming back to him, you can’t keep him out of the narrative. You still can’t.’

Wilson was the city’s late twentieth century Renaissance man with a bewildering number of roles. He was a broadcaster, impresario, writer and the owner of Factory Records, the archetypal post-punk ‘indie’ label.

After graduating from Cambridge University, instead of racing to London, he returned north where his wit and energy gained him work as a journalist and then presenter with Granada Television, at that time the most important of the UK independent TV companies. A maverick and a radical he was allowed, over time, to develop his own individual personality underscored by his commitment to pushing Manchester forward, to helping it re-invent itself and live up to its progressive past. He led and presented many programmes in his trademark forthright and opinionated style including the main regional ITV news with Granada Reports but also pioneering music shows such as So it Goes.

Factory Records allowed Wilson to emphasise his love of counterculture. With bands such as Joy Division, New Order, Happy Mondays and others he was the music critics’ darling. When the famous and subsequently notorious Hacienda nightclub opened in 1982, the legend of both Factory and Wilson was enhanced. The chaotic way in which Factory operated (or didn’t) meant Wilson, along with Rob Gretton and Martin Hannett, helped the city, during a difficult period of economic decline, develop a cool and sexy reputation away from its well-known football clubs and bleak imagery of closing factories.

The richness and complexity of Wilson’s character has led to his portrayal in movies. Manchester actor and comedian Steve Coogan played him in Michael Winterbottom’s 2002 film, 24 Hour Party People, and Craig Parkinson played him in Anton Corbijn’s 2007 film Control. Part of the attraction with Wilson as a character was his contrarianism. This made him a love/hate figure during his life, but Wilson didn’t seem to mind too much as long as Manchester was getting things done. It was partly his relentless ambition to make the city a player on the world cultural stage that was the inspiration behind Manchester International Festival.

Peter Saville, graphic designer and part owner of Factory Records, who has also been involved with the International Festival has said: “Tony created a new understanding of Manchester, the resonance of Factory goes way beyond the music. Young people often dream of going to another place to achieve their goals. Tony provided the catalyst and context for Mancunians to do that without having to go anywhere.”

Wilson would have been delighted that the square that bears his name, Tony Wilson Place, at First Street has at its centre a statue of Friedrich Engels, a German who co-wrote the Communist Manifesto and lived for 22 years in Manchester. Wilson had some German ancestry, but the fact some people and visitors think the Engels statue, given its location, is of him would have made him howl with laughter.

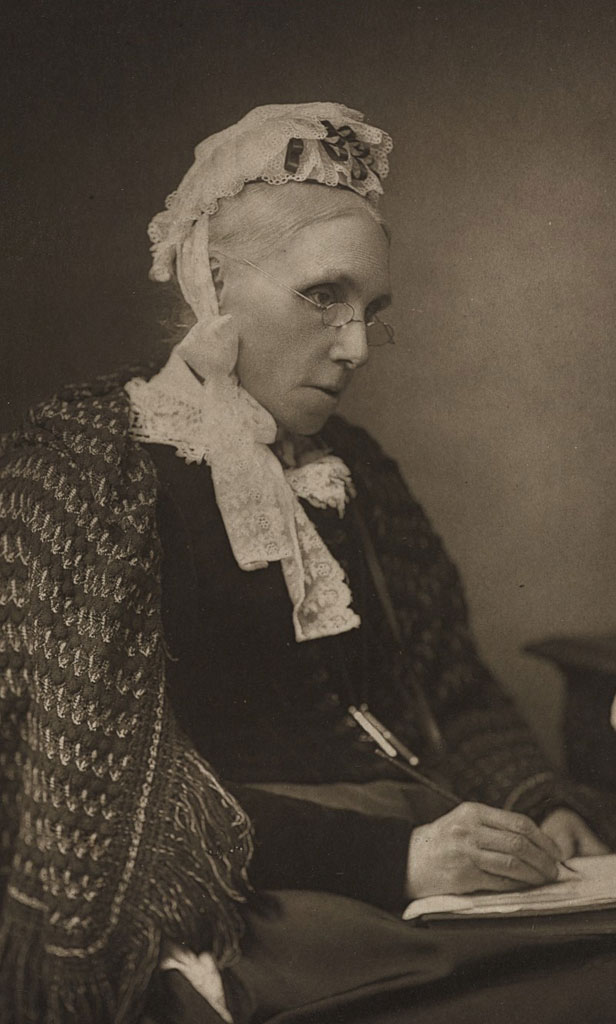

ISABELLA BANKS STREET

Isabella Varley was born at 10 Oldham Street into ‘a family of chemists who had an artistic bent’. By the age of ten Isabella showed real skill for sewing, embroidery and tatting lace. She was good and her father sold her lace caps in his store.

She became a schoolteacher publishing poetry and then in 1846 she married journalist, speaker and poet George Linnaeus Banks and took his name which included an exotic reference to the Swedish Linnaeus, the father of modern taxonomy, the naming of organisms. George had an unreliable income and they travelled around the country for work. He was also a heavy drinker which was unusual for a Methodist. Eight children were born although only three survived into adulthood.

Isabella helped support the family by writing and publishing a needlework design monthly. As George’s alcoholism became more pronounced Isabella became the main breadwinner but her health suffered. She started writing The Manchester Man during one recuperation period. It was her only real success and the work that would live on after her death.

The Manchester Man was published in three volumes in 1876 and is a fictionalised account of the growth of Manchester as the defining metropolis of the Industrial Revolution. In a grand sweep of epic storylines, it charts the rise of Jabez Clegg beginning with his rescue as a baby floating down the River Irwell in 1799, appropriately in a Moses basket. Among the many twists and turns in the book is the rivalry with Clegg’s posh nemesis Laurence Aspinall. Both are rivals for the love of Augusta Ashton. There is romance and drama but also some of the best accounts of real events written such as the Peterloo Massacre, the Corn Law riots and much else.

It is fitting Isabella Banks Street links to Tony Wilson Place as the words on Tony Wilson’s gravestone at Southern Cemetery are taken from Banks’ novel, The Manchester Man. They read ‘Mutability is the epitaph of worlds, change alone is changeless. People drop out of the history of a life as of a land, though their work or their influence remains.’

These words could apply both to Wilson and Banks.

Another, less poignant, measure of immortality maybe the fact two bars in Manchester have been named after characters in The Manchester Man, Jabez Clegg and the still operating Joshua Brooks on Princess Street named after Clegg’s eccentric school master.

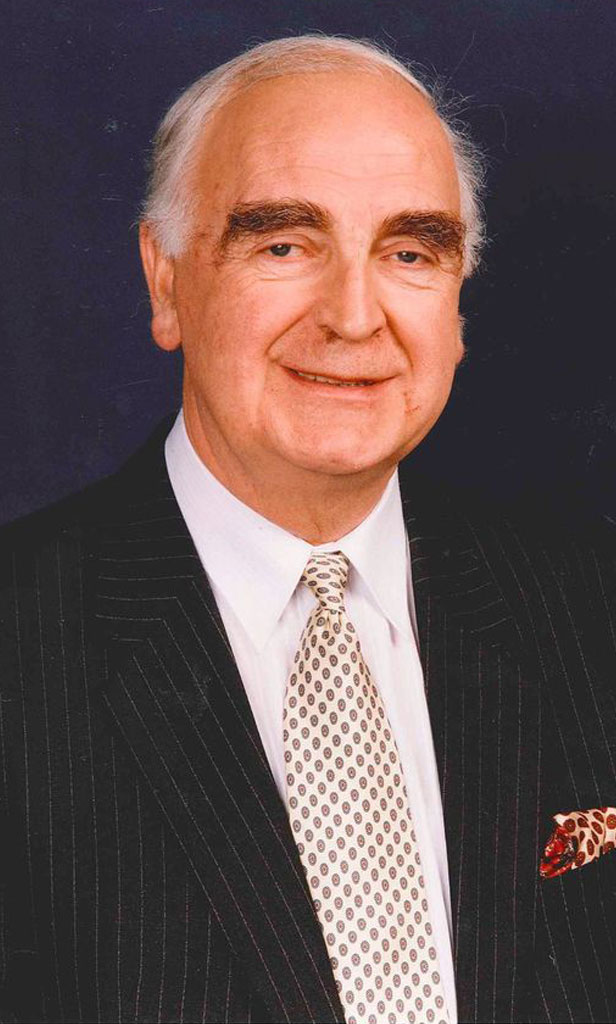

JAMES

GRIGOR SQUARE

James Grigor was born and raised in Lanarkshire, Scotland. The son of a steel worker, he went on to be a cold war rocket scientist and industrialist for the drugs multi-national Ciba Geigy before leading the regeneration of business, arts and science in Manchester.

James started out as a gifted academic with a PhD and the top first-class honours in Chemistry from Glasgow University before being recruited by ICI in the 1950s. From there he was seconded into US Naval Intelligence as a rocket propulsives expert on the military’s space and missile programme, the forerunner of NASA. Whilst still in his 20s he was accorded the rank of Brigadier General.

In 1966 he moved to the Swiss drugs company, Geigy, as a main board director – firstly as Research Director then Managing Director and Director of Corporate Planning & Development after the merger with Ciba. In 1987 he was awarded an OBE for services to industry, these achievements having been recognised some years earlier by his election to the Atheneum Club, Pall Mall and to the Royal Society of Edinburgh as a Fellow. His contribution to science and the arts had been similarly acknowledged in his being elected Fellow of the Royal Society of Chemistry and Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

During the late 1980s & 1990s James turned his attention to Manchester’s urban and cultural renaissance. He was an inspiring, innovative leader and tireless champion from his positions as Chairman of the Central Manchester Development Corporation, Chairman of the Royal Northern College of Music, Chairman of the Manchester Science Park and Chairman of the Museum of Science and Industry. It was during this time he also provided strategic vision to The Greater Manchester Police, The Manchester 2000 Olympic Bid and the Princes Trust for the North West.

Thanks to strong partnerships with Manchester City Council and the private sector, the Central Manchester Development Corporation under James’ chairmanship leaves an enduring legacy in the Bridgewater Hall, Metrolink and the regenerated districts of Castlefield, The Gay Village and The Northern Quarter which we all enjoy today.

Above all his public office, James remained first and foremost a family man. This was his greatest role and the one which gave him most pride.

A Tribute by Tom Bloxham MBE Chairman, Urban Splash – Memorial Service for the Life & Work of Dr James Grigor, Manchester Cathedral 2011

I am sorry that I cannot be with you today, but I am speaking about regeneration at an international conference in Holland and the fact that I have been invited as a so called “expert” is in no small part down to James Grigor.

I am sure you will hear more about how James very literally changed the face of Manchester; saving Castlefield from the bulldozers; building the Bridgewater Hall; creating Manchester’s vibrant Canal Street (despite a somewhat homophobic government at the time), creating thousands of jobs in the city centre and helping establish the ambition that Manchester now has as being one of the world’s great cities that we are all so proud of.

But I want to tell you all today about the influence James had on me.

I was a naive young man in my late 20’s, who had some big ideas, but little experience, track record or credibility. In 1990 I bought a near derelict building called Ducie House in a very run down part of Manchester at the back of Piccadilly railway station. The building was due to be demolished and turned into a car park. CMDC (Central Manchester Development Corporation) who obviously had a very brave (or fool hardy) chairman, refused the demolition (and I subsequently found out on very thin or no legal grounds) forcing the developers to put the building into auction, rather than demolish. I bought it prior to it going into auction with a vision of creating a home for Manchester’s growing creative industries.

It would have been so easy for the established CMDC to dismiss me as a crack pot, no hoper, idealist, inexperienced, without covenant or simply as too risky a partner, but having made a point of meeting up with the chairman, James Grigor OBE and persuading him that I had a vision and the drive to achieve it, he believed my story (and no doubt put I presume some pressure on his more sceptical officers). CMDC supported my plan for the development of Ducie House.

We hired the then young Ian Simpson to renovate the building, we filled it with loads of small businesses, including bands like 808 State and Simply Red, as well as film producers, fashion designers, artists, recording studios and graphic designers.

Ducie House has gone on to help literally thousands of businesses establish themselves in Manchester and I went onto establish Urban Splash.

Much of this is due to the faith and trust Dr James Grigor OBE put into a young and no doubt somewhat brash Tom Bloxham and I will always remember and be grateful to this great man for the start he gave me.

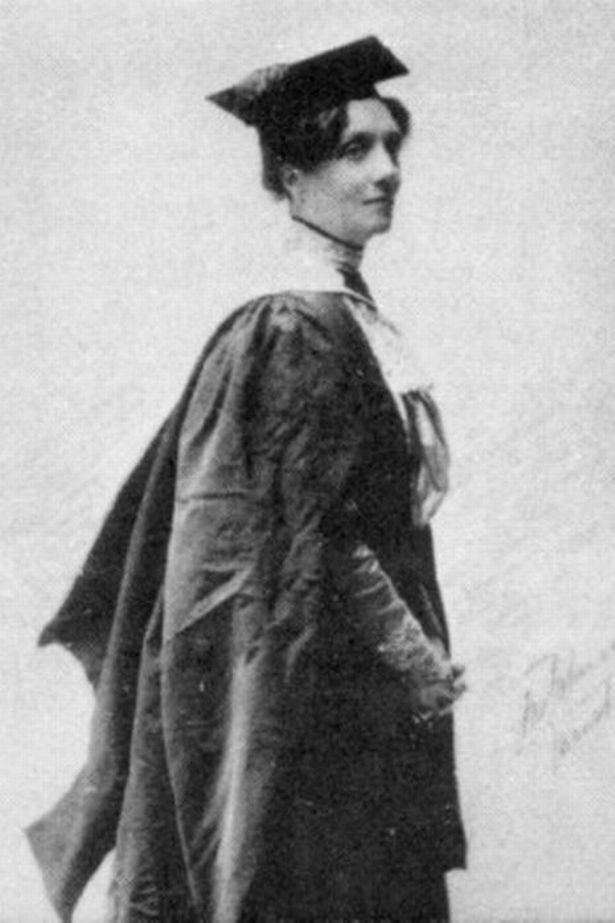

ANNIE HORNIMAN STREET

Let’s give the full name of this force of nature, Annie Elizabeth Fredericka Horniman. The daughter of a prosperous tea merchant, she studied art at Slade School of Art in London.

She developed an early love of theatre. Given her temperament and her desire to find an avenue through which to express her frustrations with society this is understandable. She was after all the model of the young independent woman of the times and fought for the women’s vote, sexual equality and sexual freedom.

Horniman was also a lover of cycling. She regularly travelled abroad alone, wearing trousers, cycling on a man’s bicycle stating “ladies’ bicycles are mere hen-roosts…serious travelling on them is ridiculous”. George Bernard Shaw was not alone in considering her trips on bikes as “monstrous and unheard of”. Horniman didn’t care.

It was on these trips she discovered the French Impressionists in Paris, while in Germany she was impressed by subsidised theatres. An admirer of the Irish poet, WB Yeats, she spent five years as his unpaid secretary. She also financed The Abbey Theatre in Dublin which staged plays by Yeats and new Irish writers.

Horniman could afford unpaid work because she had money, lots of money. In 1894 she inherited from her grandfather £40,000, more than £6m at today’s prices. Given her well-known wealth and as a nod to her father’s trade her nickname was ‘Hornibags’.

She came to Manchester in 1907 taking over the Midland Hotel Theatre. In 1908 she moved to the Gaiety on Peter Street where she was the UK pioneer of modern repertory (a repertory theatre has a permanent company of actors). She had celebrated designer Frank Matcham (Tower Ballroom, Blackpool) refurbish the Gaiety with the best sightlines and acoustics. She was involved in every aspect of theatre life, the management, the design of programmes, the reading of prospective plays. She cultivated equality too and didn’t want ‘stars’. In her view all the actors should share out roles big and small. With paid coffee breaks and other perks Horniman was known as the ‘actor’s best friend’.

At the Gaiety she produced more than 200 plays, over 100 of which were original. It was during this time the ‘Manchester School’ was formed with playwrights such as WS Houghton, Allan Monkhouse and Harold Brighouse which resulted in plays such as Hindle Wakes and Hobson’s Choice. Actors and directors included the celebrated Sybil Thorndike and Lewis Casson who eventually married. She introduced the ‘theatre of ideas’ to Manchester and the works of writers such as Henrik Ibsen.

On gala evenings Annie Horniman would travel down from her flat at 110 High Street and make a grand entrance smoking a cigar, which was considered scandalous, wearing a monocle, which was considered daring, and wearing an extravagant brocade dress, which was considered exotic. Sybil Thorndike once described her as wearing “beautiful stuff that you would only think of for curtains”. Horniman was also known for her delight in jewellery. One piece included an ‘enormous elaborate dragon pendant with ruby eyes and made of 300 opals’.

She was forced to sell the Gaiety in 1921 for £52,000 but not before the University of Manchester had conferred upon her an honorary Masters. The Gaiety inspired civic theatre in the city which led to the Library Theatre and now the theatres at HOME arts centre in First Street.

JACK ROSENTHAL STREET

The renowned dramatist Jack Rosenthal was born in September 1931 at 110 Elizabeth Street, Cheetham Hill, at that time a working-class area with a large Jewish community. His parents worked as machinists in a raincoat factory. He was evacuated during the War, first to Blackpool and then to Colne in Lancashire.

After carrying out his National Service in the Navy, Rosenthal joined the newly established Granada Television, initially writing advertising copy. But his ability to capture the characters and voices of working-class Manchester soon brought him to the attention of the drama department, where Coronation Street had just been launched. He wrote episode 31, and went on to script another 129 episodes, including, according to Corrie fans, some of the show’s most memorable scenes.

As a writer and producer at Granada, Rosenthal was involved in numerous productions. He created two comedy series, The Dustbinmen and The Lovers, and contributed to the ground-breaking current affairs satire That Was The Week That Was. In the early 1970s, he embarked on the run of feature-length television plays that would earn him widespread acclaim. He won three Baftas for Best Single Play in three consecutive years, with The Evacuees (1975), the story of his wartime evacuation; Bar Mitzvah Boy (1976), about a Jewish boy’s coming-of-age; and Spend Spend Spend (1977), the biopic of lottery winner Viv Nicholson. His Northern, Jewish working-class roots informed most of his original screenplays over the next three decades, including The Knowledge, The Chain, the TV film London’s Burning which sparked the long-running series, and (with Barbra Streisand) the movie Yentl.

In 1969, Rosenthal met actress Dame Maureen Lipman, a member of Granada’s experimental Stables Theatre Company, which was housed in the former stables of the Manchester to Liverpool Railway (now on the estate of arts space Factory International). Rosenthal and Lipman married in 1973 and had two children, writers Amy and Adam. Lipman inspired and featured in some of his best work. In 2015 she unveiled Jack Rosenthal Street, a street dedicated to him, on First Street, close to HOME arts centre; apt given his contribution to the entertainment industry.

Alongside his observant eye for the drama in everyday life, Rosenthal was a keen amateur sculptor. His subjects reflected his passion for Manchester United and included Bobby Charlton, Eric Cantona and Ryan Giggs. He listed one of his recreations as obsessively ‘checking Manchester United’s score, minute by minute’.

Rosenthal died from multiple myeloma in 2004, and was writing almost to the end.

His work is remembered for its warm humour and deep humanity. The Guardian obituary called him ‘television’s Charles Dickens, inexhaustible, ever inventive, usually scaling the heights… rarely failing to find rich comedy in every walk of life.’

Friedrich engels

Friedrich Engels was a philosopher, writer and radical thinker who was born in Germany in 1820 and died in London in 1895, aged 74. He was a close collaborator of Karl Marx in founding modern communism.

The Engels’ were wealthy cotton mill owners and Friedrich was sent to Manchester to learn about the family business. During his first twenty year stint spent here between 1842 and 1844, he observed first hand the poor working class conditions of the city which lead to the publication of The Condition of the Working Class in England.

Following the 1848 revolutions in continental Europe, and the publication of his and Marx’s Communist Manifesto, Engels returned to Manchester for a second stint, living here from 1850 for another two decades.

This 3.5m high statue was erected at First Street in 2017. The 1970s concrete image was transported to the city by the Berlin-based, British-born artist Phil Collins as part of Manchester International Festival and is now Engel’s permanent home.